ADVERTISEMENT:

The offices in Thohoyandou was locked last week.

Is this simply too good to be true?

“Is it a scam?”

An easy answer to this would be: “If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is.” To check whether the BitClub scheme is legitimate, one needs to check whether the returns promised are realistically achievable.

One investor who is now trying to get his money back says that he was promised one Bitcoin as profit after seven months. He invested in October last year and went for the top-of-the-range option, which cost him R70 800. The value of a Bitcoin varies and gets influenced by factors such as supply and demand, but in October 2018 it was around $6 320. The cryptocurrency since then took a bit of a nosedive, and in January this year it levelled out at $3 441.

Let’s take May 2019 as the date when his investment “matured” and he would have received his Bitcoin. At that stage a Bitcoin was worth $8 278. Considering the exchange rate at the time, the value of the Bitcoin would have been roughly R121 500. So, for an investment of R70 800 he would have made more than R50 000 profit in much less than a year (and he still had the investment).

To be fair to the company running the investment scheme, one needs to be more conservative and not only listen to promises made by salespeople. On the BitClub website it is stated:

“Your anticipated growth in investment is between 3 and 5% per month (based on previous performance). While BitClub does not, and never will, guarantee a return on investment, the 3 – 5 % growth per month is an expected return. Depending on the profitability of the mining, it could be higher some months, and lower other months.”

Let us take two scenarios – one with a 5% per month growth and the other on 3%. On an investment of R70 800, at 5% per month, the investment would have grown to R127 146 in one year (12 months), a profit of R56 346. On a 3% per month growth, the total would be R100 943, with a profit of R30 143.

Compare this to a “normal” investment at a commercial bank. On such an amount it should not be too difficult to get 7% interest per annum. If the interest gets paid per month, the R70 800 would have grown to R75 918 after a year, a profit of R5 118.

What is clear is that even the 3% per month return on investment alluded to by BitClub by far exceeds any investment option available from a reputable institution in the country. If the BitClub representatives are to be believed, you can easily double your money in a year. It sounds too good to be true … because it probably is.

Can Bitcoin mining generate such profits?

To answer this question, a brief discussion of the concepts involved and the factors influencing the cost of “mining” a Bitcoin is necessary. The BitClub marketers will be quick to tell you that Bitcoin mining is much the same as mining for gold or diamonds. You invest in the mining industry, meaning that certain expenses such as infrastructure and running costs are involved.

In order to mine a Bitcoin, you need a specialised computer able to do fast number crunching. The computer needs to calculate a complicated formula, which can take anything from a couple of weeks to many months. Once the computer has successfully solved the “puzzle”, a unique Bitcoin is created. If you did all the work and paid for all the expenses, the Bitcoin is yours to sell or do whatever you want with it. If the mining was done by a group, with several investors, the profits need to be shared.

The latest consensus seems to be that Bitcoin mining in South Africa was not profitable the past year. The high cost of electricity (mining for Bitcoins consumes a lot of energy) and factors such as load shedding, combined with a drop in the value of a Bitcoin, meant that the return on investment in a number of cases was negative.

Internationally, in countries where electricity is relatively cheap, Bitcoin mining can be profitable, but not excessively so. A variety of online “calculators” are available that allow users to enter variables such as the type of computer being used and the electricity consumption and cost. Getting a reasonable estimate of the profitability is then possible.

In an article that appeared on the website Mybroadband.co.za in October last year (which was when the local investor deposited his money), the earning potential of Bitcoin mining is discussed. Jamie McCane, the author of the article, used several examples of “mining rigs”. A popular choice, the Antminer D3, would need one year and 52 days of mining before it would cover its own hardware cost. In South Africa, such machines would easily run up an electricity bill of over R1 200 per month.

“Looking at the data above, it is apparent that while some users may be able to make a small profit mining digital currency, it is no longer profitable for the majority of users,” was McCane’s conclusion.

Factors such as a steep rise in the value of Bitcoin will definitely influence the profitability, but for the period that our local investor took part in the scheme, it actually fell to under $4 000, before recovering again.

How are the “dividends” then possible?

Our investor did receive money from the scheme during the first few months. He says that the membership fee ($99) was repaid and thereafter another $500. The total, in Rand value, that was paid to him, was R8 512. If it was an ordinary investment, this would have been better than what he could get at any financial institution on a risk-free option. The problem is, of course, that this is not what he was promised, and he is now also battling to get his investment back.

The only way possible to pay investors such “dividends” when the investment itself did not perform, is to pay them from money deposited into the scheme by new investors. The BitClub scheme has a strong emphasis on recruitment and offers huge incentives for referrals. This, unfortunately, is a tell-tale sign of a Ponzi scheme.

To understand what a Ponzi scheme is, one first has to look at the simplified form, the equally dangerous pyramid scheme. The difference between a Ponzi scheme and a pyramid scheme lies in the way each scheme is promoted. With pyramid schemes, the participants are aware of the fact that revenue is generated by recruiting new members. With Ponzi schemes, the participants may not always know this, and the drivers of the scheme can deceive investors into believing that a fair amount of legitimacy is involved. In both schemes, however, new investors’ money is used to pay earlier investors or the drivers of the scheme. In both cases, the scheme crashes when the cash stops flowing in.

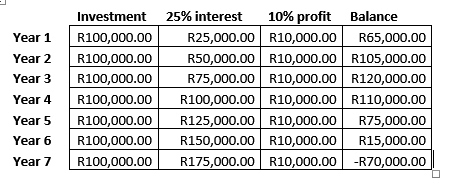

To properly explain how a pyramid scheme works, using an example would be best. Let us set up a very sedate fictitious scheme where we ask people to each invest R100. We promise them 25% interest, payable at the end of the year, as long as they leave their money in the scheme. In effect this means that, after four years, they would have doubled their money.

We will obviously not tell the investors that we have no money to start off with. Let us also presume that we convince 1 000 people per year to invest their R100 in our little scheme. At the end of the year, the bank balance stands at R100 000. The company pays R25 000 in interest to investors (R25 per person) and the directors take 10% (R10 000) for themselves, which still leaves R65 000 in the bank.

In the second year, another 1 000 people join the scheme, meaning that the interest payment has now gone up to R50 000. The directors again take a moderate 10% of new investors’ money for themselves, but the bank balance is still “fine” at R105 000 (R65 000 + R100 000 – R60 000). All seems to be well, because the early investors have received half their money back and the new investors have earned 25% interest.

|

The scenario starts changing in year four, when the amount being paid in interest and commission (R110 000) is more than the amount being deposited by new investors (R100 000). By year six, the cash reserves have plummeted to just R15 000 and in the next year the company is in debt and can no longer pay interest. Once word of this gets out, the investors start to panic and want to withdraw their money. They are in for a shock, because the money is gone.

Many experts believe that the BitClub Network is merely a sophisticated Ponzi scheme. The chances that it is in the process of falling apart seem to be quite high. At best, this is a very risky investment where the chances of investors’ losing their money are far greater than their gaining any profits.

A very interesting analysis of the BitClub Network appears on the site 99bitcoins.com. Ofir Beigel dissected the scheme, looking at factors such as where the website is registered and who runs it. He even checked the authenticity of the images of the people supposed to have endorsed the scheme. The article is well worth a read if you still plan on investing in such a scheme: https://99bitcoins.com/anatomy-bitcoin-scam-bitclub-network-analyzed/

News - Date: 24 November 2019

Recent Articles

-

New lab welcomed by Bungeni learners

20 April 2024 By Thembi Siaga -

Rialivhuwa and Sally are king and queen

20 April 2024 By Kaizer Nengovhela -

'Headman demolished my house'

20 April 2024 By Kaizer Nengovhela -

Department shuts down Ziggy School

19 April 2024 By Thembi Siaga

Search for a story:

ADVERTISEMENT

Anton van Zyl

Anton van Zyl has been with the Zoutpansberger and Limpopo Mirror since 1990. He graduated from the Rand Afrikaans University (now University of Johannesburg) and obtained a BA Communications degree. He is a founder member of the Association of Independent Publishers.

ADVERTISEMENT: