ADVERTISEMENT:

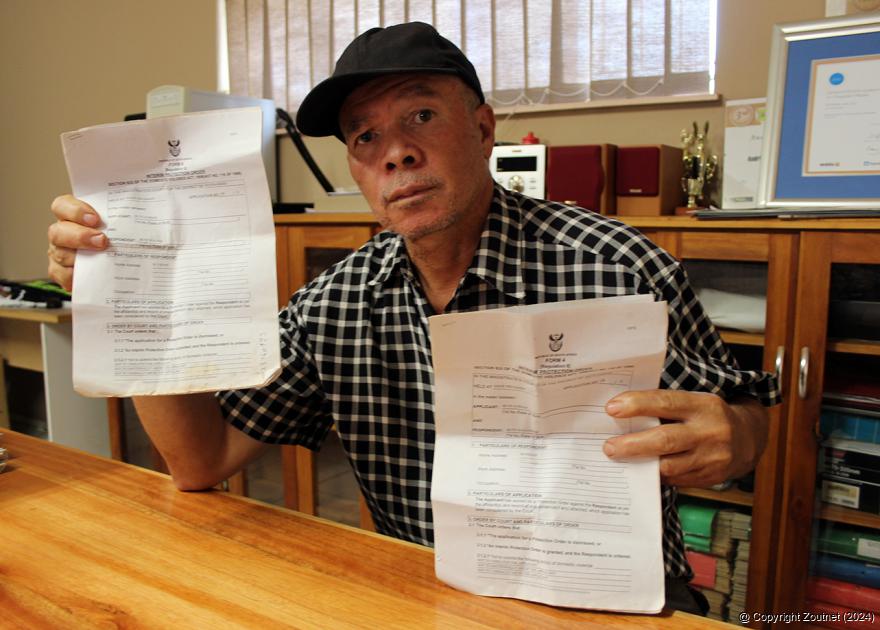

The 64-year-old Mr Aurean Buys with the two protection orders he was granted against his neighbour and his neighbour’s son. Despite the orders, Aurean said, the justice system and the police had failed him by not enforcing the orders.

A failing system?

Is a court-issued protection order, whether interim or permanent, worth the paper it is written on?

According to the 64-year-old Mr Aurean Buys of Buysdorp it is not. For many years now, problems have existed between him, his neighbour and his neighbour’s son.

Aurean said that he initially only suffered verbal abuse from his neighbour and his neighbour’s son – both relatives of his. The abuse, however, started to escalate from December 2014, with the abuse turning more violent every time. This eventually led to Aurean's applying for an interim protection order against the father and son.

Two interim protection orders, one against the father and one against the son, were issued by the court in Louis Trichardt on 5 August 2015. The same documents ordered the father and son to appear in court on 23 September of that year for the court to decide whether or not to make the interim orders permanent. Both protection orders were eventually made permanent. The protection orders clearly state that neither the father nor the son may threaten Aurean, verbally or emotionally abuse him, or make contact with him in any way.

Armed with the two protection orders, Aurean thought his problems were over. “But was I wrong! My problems were only about to start…” said Aurean.

On 5 December 2016, Aurean was employed by another family member to remove rocks from the family member’s driveway in front of his house. Shortly after starting to work, his neighbour’s son arrived and immediately started to abuse Aurean verbally once more.

Aurean finished his work and went to the Mara police station on 6 December to report the matter and have the son arrested. The protection order states under the heading "TO ALL MEMBERS OF THE SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE SERVICE" that “Therefore you are hereby authorised and ordered to forthwith arrest the respondent in terms of the provisions of the Domestic Violence Act, 1998, if there are reasonable grounds to suspect that the Complainant may suffer imminent harm as a result of the alleged breach of the protection order by the Respondent.”

Still hoping that the piece of paper would protect him, Aurean said that the police merely informed him that they would go and talk to the son. “Two days later, I saw a police vehicle pick him up and I assumed they had arrested him,” said Aurean.

But this was not the case, much to Aurean’s dismay. “It turned out the police didn’t arrest him, but took him to the court at Tshilwavhusiku, where they assisted him to obtain an interim protection order against me!” said Aurean. Aurean found this out on 9 December after receiving a visit from the Mara police to inform him that he was due to appear in court in Tshilwavhusiku on 13 December.

Aurean was outraged at this, and on 12 December he went to the station commander at Mara to voice his dismay about the police’s handling of the case. “The police refused to assist me, nor did the station commander want to see me. It was only after making a huge scene that the station commander came out of her office. She told me that she was very busy and asked me what I wanted,” said Aurean.

Aurean explained the situation and was somewhat surprised that the station commander had no knowledge of the protection orders, despite Aurean's pointing this out to police members on several occasions. “She told me to go and get the protection orders from my home and, after returning to the police station, I was eventually assisted in opening a case and a subpoena was issued against the neighbour's son to appear in court on 12 January this year for the violation of the protection order against him,” said Aurean.

On 12 January, said Aurean, the case appeared before a local magistrate at the Mara police station. Again, his efforts to enforce the protection order hit a brick wall. The accused, said Aurean, demanded that his attorney be present and then “could not get hold” of his attorney. Following this, the case was postponed indefinitely until a new court date could be set. This left Aurean at the mercy of his abusive neighbours once more, despite the protection order.

Aurean believes in following procedures, but said that the justice system and police had failed him. He added that he thought the reason why the Mara police were reluctant to assist him was that the father of the neighbour’s son was a retired policeman who had been stationed at Mara. “What is the use of a protection order if the police do not enforce this court order? I can see why people eventually take the law into their own hands,” said Aurean. He was referring to the Alexander Smail double murder that occurred in Buysdorp.

The 65-year-old Smail handed himself over to the police shortly after shooting and killing Cornelius Bruce Joachim (20) and Sergio Bozario Buys (21) in front of his shop in Buysdorp in December 2009. He was eventually convicted of the two murders in October 2014 and was sentenced to six years' direct imprisonment in March 2015. Smail appealed against his sentence, however. Throughout his court case and appeal process, Smail argued that he had not meant to shoot the two and had acted in self-defence. Smail argued, among other things, that much of what happened on the fateful day in December 2009 could be attributed to frustration over the chronic break-ins at his store and the Mara police’s failure to assist or help him. Smail’s appeal was successful. In May 2015, Judge E M Makgoba overturned the murder convictions against Smail and in June 2016 he was released a free man.

Aurean said that he believed that the police’s failure to act, as in the Smail case, eventually led to people's dying.

Another example of where the police’s handling of an interim protection order case had possibly led to another two people's being shot dead, was in October 2014. Ms Mapula Darlene Madiba (34) and her friend, Mr Victor Mthokozisi Radebe (36), were gunned down in cold blood at Madiba’s home in Duiker Street, Louis Trichardt, on 13 October of that year. Shortly after the double murder, the police arrested Madiba’s ex-boyfriend, Vincent Teboho Moabelo, and he was charged with the two murders.

It later transpired that Madiba had been granted an interim protection order again Moabela and that the order was to be made permanent on the day of her death. On 4 August 2014, Madiba was granted the interim protection order by the Louis Trichardt District Court, after Moabela had allegedly viciously assaulted her. Madiba had informed the court that Moabelo had also threatened her with his licenced firearm and that she feared for her life. Assault charges were laid against Moabela and the Makhado police seized his pistol.

The assault case was also heard in the Louis Trichardt District Court and it was agreed that Moabelo would pay an admission-of-guilt fine on 16 September. About two weeks before the payment date, however, Moabelo’s firearm was allegedly returned to him by the Makhado SAPS. According to law experts, Moabelo’s firearm could only have been returned to him by the police in terms of a court order after he had paid his fine, or if the police had agreed to do so. Following the double murder, the police indicated that they had opened an investigation to find out why Moabelo’s firearm had been handed back to him.

Aurean’s story was referred to the provincial police for comment as it would seem that the police do not take the issue of protection orders very seriously, especially seen against the background of the Madiba double murder. The case also begs the question whether the police are adequately trained to handle and understand the seriousness of a protection order against a person? The Zoutpansberger also wanted to know whether the provincial police would investigate Aurean’s complaints against the Mara police.

In response, the police’s provincial head of communication and liaison, Brigadier Motlafela Mojapelo, re-assured the public that the police viewed the enforcement of the law regarding protection orders in a very serious light. “The police members are adequately trained in handling any domestic violence report, hence our members attend courses on the Domestic Violence Act. 116 of 1998,” said Mojapelo.

At face value, it would seem that the Mara police had not acted in an appropriate manner by not arresting the neighbour’s son after Aurean’s complaint. “When a complainant reports a violation of any stipulation in the protection order to the police, we are obliged to arrest. Any allegations of failure to do so should be brought to light for the matter to be addressed in time,” said Mojapelo. Having brought the matter to light and upon asking whether it would be investigated, Mojapelo said that the question fell within internal disciplinary processes. “We are therefore unable to respond to this question as matters between an employer and employee are not discussed in the media,” Mojapelo said.

News - Date: 27 February 2017

Recent Articles

-

New Lukwarani leader may be blind, but has bright vision for his people

14 April 2024 By Elmon Tshikhudo -

Teach women to farm and they will change the world, says young farmer

14 April 2024 By Anton van Zyl -

-

Elim family fed-up with VDM's inability to fix sewer

13 April 2024 By Kaizer Nengovhela

Search for a story:

ADVERTISEMENT

Andries van Zyl

Andries joined the Zoutpansberger and Limpopo Mirror in April 1993 as a darkroom assistant. Within a couple of months he moved over to the production side of the newspaper and eventually doubled as a reporter. In 1995 he left the newspaper group and travelled overseas for a couple of months. In 1996, Andries rejoined the Zoutpansberger as a reporter. In August 2002, he was appointed as News Editor of the Zoutpansberger, a position he holds until today.

Email: [email protected]

ADVERTISEMENT: